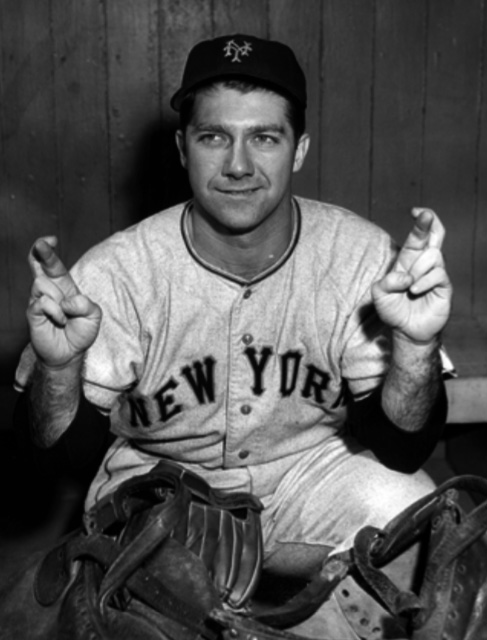

In 1947, journeyman infielder Hank Schenz joined the Nashville Vols and split the season with newcomer Buster Boguskie at second base. Schenz’s story continues with the Chicago Cubs and Pittsburgh Pirates, but in 1951 the New York Giants purchase his contract and he becomes a back story to Bobby Thompson’s “shot heard ’round the world.”

Note: This biography appears in “The Team That Time Won’t Forget: The 1951 New York Giants” (SABR, 2015), edited by Bill Nowlin and C. Paul Rogers III. Purchase your copy here: https://www.amazon.com/Team-That-Time-Wont-Forget/dp/1933599995

Henry “Hank” Schenz was claimed off waivers by the New York Giants from the Pittsburgh Pirates midway through the 1951 season, setting in motion a unique connection to the most famous event in baseball history. As told by Joshua Prager in The Echoing Green: The Untold Story of Bobby Thomson, Ralph Branca, and the Shot Heard Round the World, manager Leo Durocher discovers that Schenz’s prowess with a spyglass might also be used to the team’s advantage.[1]

The events that led up to the historic pennant-winning home run by Bobby Thomson include a hidden weapon: Schenz owned a Wollensak telescope. He had used it before to spy for signals from the center-field scoreboard at Wrigley Field.[2] Durocher would put the practice to good use.

James L. “Jim” Schenz, Hank’s eldest son, explained why his father had a telescope in the first place. “Dad had no interest in astronomy. In those days, everyone was looking for signs. That’s the reason.”[3]

The Hank Schenz story begins much earlier. He was born on April 11, 1919, in New Richmond, Ohio, a village nestled 20 miles southeast of Cincinnati along the banks of the Ohio River. His father, also Henry, was a rural mail carrier and was the head of the American Legion post in Clermont County. The elder Schenz served as a private in the 379th Infantry, Company H, beginning in 1919.

Hank’s father was a strong influence in his life. Jim Schenz explained, “His father was a strict authoritarian, and my father did not contradict him. If my grandfather said, ‘The crow is white,’ our family was to have believed the crow was white.”

A 1937 graduate of New Richmond High School, Hank turned down a scholarship to play college ball.

“Even though he was offered a full-ride at the University of Cincinnati, he was signed by the Cincinnati Reds and was later traded to the Chicago Cubs,” Jim said.

Scout Frank Lane signed Schenz to a contract in 1938 after seeing him play semipro ball in Louisville, Kentucky, and Aurora, Indiana.[4] Lane liked his speed.

“[H]e could run and holler,” Lane told the Reds.[5]

Cincinnati sent Schenz to the Union City (Tennessee) team in the Kitty League. Perhaps a precursor to nagging injuries throughout his career, a broken thumb cut short his first season, and he didn’t make his Organized Baseball debut until 1939, playing for the Salem-Roanoke Friends in the Virginia League (Class D) as a 20-year-old second baseman. He played in 83 games and hit a respectable .312, but made 28 errors.

Assigned to Tarboro, North Carolina, in the Class D Coastal Plain League in 1940, Schenz proved to be an adequate hitter with a .328 average. Traded to the Chicago Cubs from Tarboro before the 1941 season, Schenz moved up two classifications to the Cubs’ Piedmont League (Class B) team at Portsmouth, Virginia. He remained there for the 1941 and 1942 seasons, playing second base and shortstop. His batting average dropped dramatically to .246 and .243.

At the age of 24, Schenz enlisted in the US Navy on September 24, 1942, and was sent to the Norfolk (Virginia) Naval Training Station. With experience as a postal worker for his father, he was assigned to the mail room. But as often was the case for professionals who had joined the military, he played baseball in Norfolk.[6]

Tragedy struck Schenz’s family on March 24, 1944. His father and his mother, Lucille, were killed when their car collided head-on with another automobile. His sister Gloria, 16, suffered a broken leg.

After his parents’ funeral, Schenz returned to the Norfolk mailroom. On June 10, 1944, he had a double and three singles, scored five runs, and stole two bases for the Training Station team.

Assigned to Hawaii in 1945, Schenz continued to play baseball and learned to play golf before being discharged on December 14, 1945.

Schenz began the 1946 season with the Cubs’ top affiliate, Los Angeles of the Pacific Coast League. When Angels third baseman Elmer “Rabbit” Mallory reinjured an ailing leg, rookie Schenz got a chance to play. That did not last long, as Double-A Tulsa soon became his baseball home for the year, and he had an MVP season. He batted .333 (second only to Dale Mitchell) with a league-leading 44 doubles. He also set a Tulsa record by swiping 32 bases.

The Cubs called Schenz up for the last few weeks of the season. He played in six games and had two hits in 11 at-bats, with one run batted in.

Nashville, the Cubs’ other Double-A affiliate, was the next stop for the scrappy infielder after three early-season appearances with the Cubs. In the first 26 games to begin the 1947 season the Nashville infield had committed 50 errors, and manager Larry Gilbert was happy to have Schenz.

“With his hitting, his speed, his arm and his defensive ability, Hank Schenz may be the best all-round player Nashville has had since Ed Sauer,” a Nashville sports reporter wrote.7 The comparison was daunting: In 1943 Sauer had led the Southern Association in batting average (.368), runs (113), doubles (51), and stolen bases while rapping out 200 hits.

Schenz played in only 99 games during the season, as an elbow injury sidelined him on May 15. He returned to the lineup on June 16, but tasted misfortune again on July 8 when he was spiked by Memphis second baseman Bert Hodges. He was hitting .359 at the time, and the injury included a broken bone in his ankle. On August 5, during Nashville’s ninth consecutive victory, Schenz suffered another spike wound while attempting to tag out Memphis’s Ted Kluszewski.

After finishing the Nashville season with a .331 average, Schenz was called up to Chicago, and he was expected to vie for the third-base position with Peanuts Lowrey in 1948.

By April neither Schenz nor Lowrey had satisfied manager Charlie Grimm. The Cubs revised their infield drastically; Schenz was moved to second base and Lowrey returned to the outfield. On May 31 he was hitting .313 but he tailed off badly. In early August, the Cubs claimed Emil Verban off waivers from the Cardinals and Verban started at second base for the rest of the season. Schenz finished the season with a .261 batting average.

On August 13, with the Cubs playing in Cincinnati, the 5-foot-9, 175-pound Schenz hit the first of his two major-league home runs, off southpaw Kent Peterson.13 The round-tripper came on a day when friends from the Keith Ross American Legion Post of Aurora, Indiana, honored Schenz, presenting a wristwatch, a savings bond, and luggage to him.

Jim Schenz recalled an unusual story his father told him: “In one game playing second for the Cubs, my father ran out for a fly ball and even though the outfielder called dad off of it, they collided, and the outfielder suffered a broken collarbone. His manager told him he hustled too much. Dad told him, ‘If you don’t want guys who hustle, then you don’t want me.’”

Verban was at second base and veteran third baseman Frankie Gustine was acquired after the 1948 season. After playing in only seven games in 1949, Schenz was traded on May 16 to the Brooklyn Dodgers for infielder Bob Ramazzotti and $35,000. The Dodgers optioned him to Triple-A St. Paul (American Association).[7]

At second base in 107 games for the Saints, Schenz hit .345 and slugged a career-high 17 home runs even though he did not join the club until a month into the season. Also playing the outfield for 11 games, he suffered an ankle injury and was shelved for two weeks during the season, but made the league’s all-star team.

Once again, hopes were high for Schenz. Near the end of the Saints’ season, manager Walter Alston said Schenz was one of the smartest baserunners he had ever seen. But on November 4, 1949, Schenz was sold to the Pittsburgh Pirates, whose general manager was now Branch Rickey. Rickey had acquired Schenz for the Dodgers the season before while he was still with Brooklyn.

Schenz failed to win a starting job with the Pirates but caught on as a utility infielder, bouncing between second base, shortstop, and third base. On June 3 at Pittsburgh’s Forbes Field in one of his rare starts, he led off the Pirates’ first inning with a home run off Johnny Sain. He played in a total of 58 games and batted .228. Early 1951 brought more of the same. Seeing little action and after playing in only 25 games, on June 30 he was sent on waivers to the New York Giants.

A transaction that did not occur could have changed the course of history: The Sporting News reported on August 15, 1951, that the Minneapolis Millers’ general manager, Rosy Ryan, sought to acquire Schenz from the Giants, the Millers’ parent club, but “at the last minute the St. Louis Browns blocked the move by entering a claim for Schenz.”17 Schenz could have taken his Wollensak telescope to St. Louis Browns manager Zack Taylor instead of Durocher. The Browns were out of the running and finished the season 52-102. The Giants, however, accomplished the feat of winning the pennant in a three-game playoff with the Dodgers after going 50-12 for the last part of the season to tie Brooklyn at the end of the schedule.

The dream finish by the Giants and the subsequent World Series marked the end of Schenz’s major-league career. With the Giants he got into eight regular-season games, all as a pinch-runner. The last was on September 13. His only World Series appearance was in Game Two, as a pinch-runner for Wes Westrum as the potential go-ahead run in the seventh inning. The New York Yankees won the game 3-1 and eventually won the World Series title in six games over the Giants.

On December 4, 1951, the Giants sold Schenz’s contract to the Oakland Oaks of the Pacific Coast League. Sportswriter Arch Murray appropriately commented in The Sporting News, “It was with a pang of regret that they let him go, because all hands at the Polo Grounds believe he played a vital role in the spiritual life that enabled the Giants to make their tremendous drive down the stretch.”

Schenz got off to a good start with Oakland, but he just could not avoid injuries. Hitting at a .332 clip after 52 games, on June 20 Schenz suffered a sprained wrist while sliding into a base. A week later he was hit in the face by a ball during infield practice. Unable to start the game, he was sent up as a pinch-hitter by Oaks manager Mel Ott in the fifth inning and singled in two runs in a 3-1 victory over the San Francisco Seals.

After being benched for a while in July because of a batting slump, Schenz hit a bases-loaded triple in a 7-3 win over Seattle on the 17th. A month later he suffered an ankle injury and was out again. Frustrations seemed to show, as Ott benched Schenz on August 30 after he had been picked off twice earlier in the week and bunted foul on a third strike against Ott’s orders. But Schenz was back in the lineup in the nightcap of the next day’s doubleheader and batted in five runs in a 12-5 win over the Seals.

Once the season ended, Schenz and teammate Piper Davis, a veteran of the Negro Leagues, played with the Patriotas de Venezuela team in the Venezuela League. On October 19 he hit the league’s first home run of the season.24 Hitting .308 on October 27, the next month he raised his average to .422. By December 8 Schenz had moved to first place in the batting race (.385), but he had set a league record by hitting safely in 22 consecutive games. On December 21, his hitting streak was stopped at 27, a hit in every game he had played in up to that point.[8] Schenz finished with a .355 average for the 1952-53 season and both he and Piper Davis were selected to play for Caracas in the Caribbean Series.

Returning to Oakland for 1953 at the age of 34, Schenz played in 32 games before being traded with pitcher Milo Candini to Sacramento for pitcher Jess Flores and infielder Ray Dandridge. On May 27, another setback ended his season; he fractured his collarbone in a collision with Seattle baserunner Ray Orteig as Schenz attempted to field a groundball.

In September, his injury mended, Schenz played winter ball again, this time for Navegantes del Magallanes in Puerto La Cruz, Venezuela. He did not have the same success as in the previous year, batting.258.

Back with Sacramento again in 1954, Schenz had eight home runs by June 22 but finished the season with only 11. On August 1 he made his pitching debut in the ninth inning of a game in which he allowed two runs on two hits. He had a 15-game hitting streak in August. On August 25 Schenz missed his first game of the season with a sore leg. At season’s end, Schenz’s batting average was .279 and he was nearing the end of his playing career.

Schenz began the 1955 season in Sacramento but on May 1 he was named manager and part-time third baseman of the Tulsa Oilers, a Cleveland farm team in the Texas League, replacing Dutch Meyer. The team was firmly entrenched in last place when he took the reins, having lost 17 of its first 21 contests under Meyer. By June Tulsa had won 18 out of 22 games and 15 of 16 home tilts, moving out of last and into second place in the standings. During their June rush, the Oilers won 33 and lost 19.

With 20-year-old Roger Maris on the roster and led by Joe Macko’s 28 home runs and 102 RBIs, the Oilers finished 86-75, good enough to tie with Houston for fourth place. Schenz played in 51 games for the Oilers, pitching five times.

After the Tulsa season Schenz retired and settled in the Cincinnati area once again. According to his son, he often pitched batting practice for the Reds at Riverfront Stadium.

“My father and Sparky Anderson had become friends in the Texas League, where Sparky was playing second base at Fort Worth and Dad was at Tulsa,” Jim Schenz said. “Sparky would invite him to come down (to Cincinnati) to help him out. Dad lived at Deer Park, Ohio, a suburb of Cincinnati, and it was only a 20-minute drive to the ballpark.

“Dad admired Pete Rose, too, because that’s how he played.”

Hank Schenz died of a heart attack on May 12, 1988, in Cincinnati at the age of 69. He was survived by his wife, the former Betty Jane Claus, whom he had met in Aurora, Indiana; two sons, Jim, and Jerald; and a daughter, Susan Ehasz. He is buried in Green Mound Cemetery in New Richmond.

“When Dad’s baseball career ended, it just ended,” Jim Schenz said. “At almost 70 years of age in 1988 as a member of the Queen City Umpires Association, he umpired a high-school doubleheader and afterwards was not feeling well and passed away.”

Ohio sportswriter Jim Bishop reminisced: “One of the best bench jockeys of all time was Hank Schenz, who never stopped shouting from the start of the game to the finish. … He not only riled the opposition, but he pitched batting practice, caught batting practice, and swept out the dugout.

“(Pirates manager) Bill Meyer said: ‘Schenz can do anything but play regular.’”[9]

Circumstances and injuries prove Bill Meyer right.

Sources

In addition to the sources noted, the author also used online sources at Retrosheet.org, Baseball-Reference.com, Ancestry.com, Baseball-almanac.com, Purapelota.com (Professional Venezuelan Baseball Statistics), The Sporting News, and Oaklandoaks.tripod.com.

Rod Nelson provided Schenz’s Howe Bureau Card (courtesy of Bob McConnell).

Notes

[1] Joshua Prager. The Echoing Green: The Untold Story of Bobby Thomson, Ralph Branca, and the Shot Heard Round the World (New York, Vintage Books, 2006).

[2] Andrew Goldblatt. The Giants and the Dodgers: Four Cities, Two Teams, One Rivalry (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2003).

[3] Jim Schenz, telephone interview, March 7, 2014.

[4] Howe Bureau Card, courtesy of Bob McConnell.

[5] Prager, 19.

[6] Fred Russell, “Sideline Sidelights,” Nashville Banner, May 15, 1943. Ed Sauer was Hank Sauer’s brother.

[7] In the May 27, 1949 edition of The Sporting News, sportswriter Red Smith termed the cash amount “a bundle of boodle.”

[8] Lou Hernandez. The Rise of the Latin American Baseball Leagues 1947-1961 (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, 2011), 332.

[9] Jim Bishop, Lancaster (Ohio) Eagle-Gazette, October 1, 1962.

© 2015 by Skip Nipper. All Rights Reserved by Skip Nipper