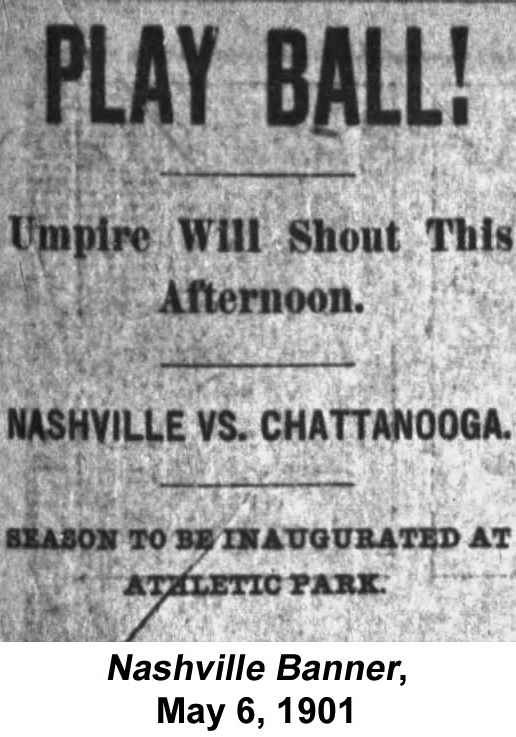

Began Play in 1901

In 1900, the Southern Association of Baseball Clubs was organized by Newt Fisher, Charles Frank, and Abner Powell. At a meeting in Birmingham on October 20 of that year, franchisees were granted to six cities to begin playing in 1901: Nashville, Chattanooga, Memphis, Shreveport, New Orleans, and Birmingham.

Applications for putting a team in the new league were from Atlanta, Montgomery, Little Rock, and Mobile. Little Rock and Atlanta were eventually accepted, but in February of 1901, Atlanta’s franchise was awarded to Selma.

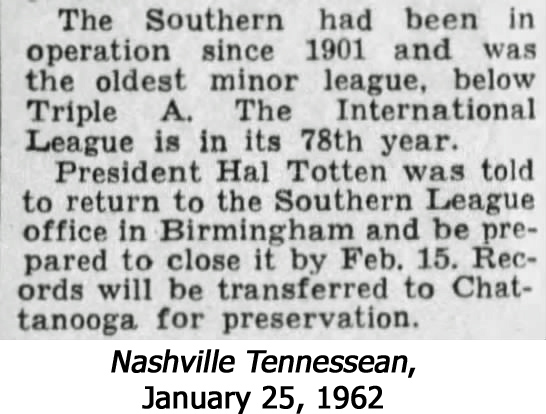

Thus began the illustrious history of the Southern Association, a league that would last 60 years until folding at the end of the 1961 season. At a board meeting held in Charlotte in January 1962, the directors announced that the league would officially suspend operations on February 15.

Failure to Integrate

Why would a league fail after surviving two World Wars, the Depression, the Korean Conflict, multiple franchise re-locations, and decaying grandstands?

The obvious explanation was segregation. There was no league rule that anyone has discovered that said teams could not use black players. In 1953, Atlanta experimented with integrating the Crackers by inserting Nat Peeples in a game as a pinch hitter Mobile (the owner of Atlanta, Earl Mann, was not quite brave enough to let Peeples play in Atlanta). The next day Peeples played the entire game, but after a week, is sent to Jacksonville.

Reportedly Mann considered the same action the previous season with a different negro player playing in Jacksonville: Henry Aaron. For whatever reason, the future Hall of Famer was not selected and had an outstanding season with the South Atlantic League club.

But civil rights issues were coming to the forefront of American culture, and integration never occurred (or were late to the dance). For example, a Birmingham city ordinance prohibited integrated games on city-owned fields. Louisiana state law did not allow different races to participate in sporting events together.

Gabe Paul, Cincinnati Reds GM

One occurrence brought attention to the situation: in August of 1960, after six years as the parent organization of the Nashville Volunteers, Cincinnati withdrew its affiliation. Without negro players, said Reds GM Gabe Paul, the development of potential players could not properly take place.

In his August 30, 1960 Sports Showcase column, Nashville Tennessean sports writer F. M. Williams quotes Paul on the issue:

“Having a team in the farm system, at Double A level, where Negro players cannot perform creates a void that hinders the entire player development program, he says. Player development is expensive at best, and it becomes even more so when there is one link in the chain that does not help the best young players.”

Williams’ opening lines in his column predict a dim future for the troubled league, emphasizing a rule (unwritten or not) of segregation and acknowledging the tension in race relations:

“If Gabe Paul’s thinking is in line with that of other major league executives, time is running out on Double-A baseball.

“Paul took a public stand against the Southern league’s policy of not using Negro players. This is the first time, to my knowledge, that any-big league executive has used the racial issue to establish farm policy.

“Eventually it could lead to a Southern boycott.”

The American League added two teams in 1961: Los Angeles and Washington, D. C. On August 31, the Tennessean published an Associated Press story that the National League announced plans to expand to 10 teams by 1962; Houston and New York would become members of the league.

Gabe Paul knew of the plans, which certainly would change the course of developing players, it appears he did not let the directors of the Nashville club know.

Minor League Attendance was Waning

One-sixth of the workforce in the United States worked directly or indirectly in the automobile industry in 1960. The growth of automobile sales could be attributed to the widening of the city limits in a growing nation. It was no longer necessary to live within walking distance of the ballpark; just hop in your new four-door sedan, and a family could be rooting for the home team in a matter of minutes.

There was another option: Lucy and Desi were on. So were George and Gracie and a host of other stars who made people laugh all from the comfort of home. No need to sit in the stadium for entertainment, a family couch was just fine. And it was hot at the ball game. Sunday was when the ball club played doubleheaders. It wasn’t too bad when games were scheduled at night, but at 1 PM for a doubleheader or an evening game in the sweltering heat? The players might have to be there, but the spectators did not.

Where it was not hot was at home. Over a million air conditioning units were sold in 1953. Watching “I Love Lucy” in the comfort of one’s den was a lot more relaxing. Why head out to the ballpark to root for the Vols when it was a twenty-minute drive, and there was a cost to park, and it was going to be hot and muggy? Besides, didn’t “Father(s) Know(s) Best”?

League Falls Apaprt

A fire that destroyed Russwood Park took Memphis out. The sale of Pelican Stadium so a huge motel could be built on the site virtually eliminated baseball in New Orleans. Atlanta got the idea the Georgia metropolis was too big for the Southern, forgetting historic Ponce de Leon Park. Shreveport and Mobile decided not to remain in the league.

By season’s end, one of Williams’ predictions had come true, as time ran out on Double-A baseball. Attempts to revive the league went for naught, even though on October 31 a federal judge ruled that Birmingham, Alabama, laws against integrated playing fields were illegal, eliminating the last barrier against integration in the Southern Association.

Birmingham was rumored to be moving its franchise to Montgomery, Huntsville, or Columbus, Georgia. Barons owner W. A. Belcher would not remain in Birmingham due to the enforcement by city officials prohibiting mixing of the races in athletic contests, even though the law has been ruled unconstitutional by a federal court. The fear of mixing black and white athletes caused Birmingham to withdraw.

If it was to continue, operating as a six-team loop became a real possibility. Not only was it difficult to navigate through the question of playing black players (in September the board of directors of Nashville had voted to include negroes beginning in 1962), finding major-league affiliations continued to be another issue. Chattanooga (Philadelphia Phillies), Birmingham (Detroit Tigers), and Little Rock (Baltimore Orioles) had affiliations, but Nashville and Macon did not.

When Belcher decided to withdraw the Barons from the league, two cities were needed. The Los Angeles Dodgers would attempt to place a team in Evansville, Indiana, and the Minnesota Twins would do the same in Columbus.

But the key was Nashville’s inability to round up a major-league club to supply financial support and players. The final discussion about survival in Nashville, a last-gasp solution, was actually for the Vols to take over the Barons-Tigers agreement.

Death Knell

On January 24, 1962, the Southern Association suspended operations “due to a lack of enough major league working agreements.”

The segregation of teams was not an issue in many other cities (Jacksonville, for example, which had minor league baseball since 1946). So, what else could be the reason or reasons? The automobile, television, air conditioning? Major League expansion and the lack of affiliations?

I argue that all factors led to a decrease in attendances, the ultimate culprit in 1961, just like it is in 2017. For example, during the 1961 season, the average attendance for all Southern Association games was less than 1,000 fans. Attendance at Nashville games in aging Sulphur Dell fell from a record-high of 269,893 in 1948 to 99,271 in 1960. That’s a decrease of over 63%.

With rapid attendance depletion between 1947 (when organized baseball was integrated) and 1960, when the death knell began to sound for the league, the rumblings of change were not new, and in 1962, organized minor league baseball is reduced to only 19 leagues from a high of 59 in 1949.

Team owners did nothing to integrate the storied league, but waning attendance was the final culprit in its demise.

Author’s note: This was presented on March 3, 2017, at the 14th Annual Southern Association Conference at Rickwood Field, Birmingham, Alabama

Resources

Fenster, Kenneth. NINE: A Journal of Baseball History and Culture, Volume 12, Number 2, Spring 2004 Earl Mann, Nat Peeples, and the Failed Attempt of Integration in the Southern Association

Johnson, Raymond, One Man’s Opinion Column: “Sadler Spins Like a Reel After Closing Tiger Deal,” Nashville Tennessean, November 30, 1961, p. 30.

Watkins, Clarence. Baseball in Birmingham. Charleston, South Carolina: Arcadia Publishing, 2010.

Wright, Marshall D., The Southern Association in Baseball, 1885-1961. Jefferson, North Carolina: MacFarland & Co., 2002.

Nashville/Davidson County Metro Archives

Newspapers.com

PaperofRecord.com

SABR.org

© 2022 by Skip Nipper. All Rights Reserved.