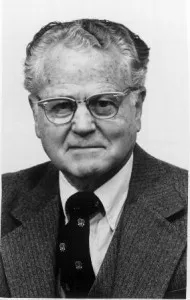

Perhaps no sportswriter had more insight to pass on to his readers than Nashville’s Fred Russell. The beloved journalist had a following who believed him, who relied on him for the inside story and insight that went beyond the box score and stats.

On more than one occasion, the sports editor of the Nashville Banner ponders the future of baseball. In the 1950s and ’60s, he would sorrowfully describe the fall of minor league’s baseball franchises. Ultimately he would lament the loss of the Southern Association after the 1961 season; two years later, the beloved Nashville Vols would disappear, too. And he would name the reasons (more to come).

It was a different story two decades earlier when night games were rapidly replacing those played in the played afternoon. Nashville had seen attendance boom from 99,615 in 1932, 113,292 in 1934, to 138,602 in 1940 before the United States entered the fray across the oceans.

By 1942 the country was fully at war. But Russell felt there was more money flowing than for any period since the Great Depression.

Quoted in the January 15, 1942 edition of The Sporting News, the prudent scribe said, “There’s more employment. Factories are running night shifts. Many men are looking for afternoon recreation. We still have the 40-hour week in most occupations. That means plenty of time for relaxation.“

Night baseball had was common in minor league team’s schedules, and there was some conversation about reducing the number of them while the country was fighting overseas. Russell seems to struggle with his reasoning for day games or night games.

He had sensed a new interest with positive results. With more games at night, fans depended on radio broadcasts when they could not get to the ballpark. He felt that fact alone gained interest from a new fan: women.

Lights added to Sulphur Dell in 1931 allowed for the first regular-season night game on May 18. It drew approximately 7,000 fans to the contest against Mobile; Nashville lost 8-1.

But as he names reasons for playing games after dark, Russell questions whether there may be day games again.

“Suppose night baseball is banned in the Southern Association and other leagues this summer, and they only play in the afternoons. Will enough people come to the parks to enable clubs to make expenses?“

“And with the rationing of automobiles and tires, there’ll be fewer motor trips, less partying, more of the old forms of amusement.

“Maybe day baseball in the minors is gone. I’m not saying it isn’t. But remember the railroads – ten years ago. Did anyone foresee the booming business of 1941 and 1942, with not an idle car in the yards and freight trains a half-mile long?

“Of course, the war is mainly responsible. And that’s what I am getting around to, the matter of whether the war may be responsible for some other comebacks. In particular, day baseball.”

At the end of 1942 season attendance stood at 96,934, so there must be some truth to the reasons the Russell listed about what people were able to do. In 1944, with hopes that the war would soon be over, attendance skyrocketed to 146,945.

Russell’s thoughts from both sides of the day or night question only helped to prove that either way, he had it figured.

© 2019 by Skip Nipper. All Rights Reserved.