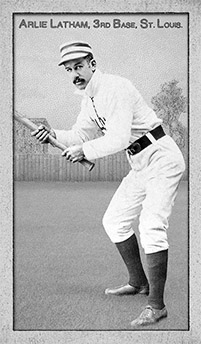

Walter Arlington “Arlie” Latham was a steady third baseman for Chris Von der Ahe’s St. Louis club in the American Association for seven seasons (1883- 1889). With four consecutive pennants beginning in 1885, Latham provided basepath punch as a great base stealer.

In 1883 he led the league by playing in all 98 games as the Browns lost the pennant to the Philadelphia Athletics by one game. In 1886 Latham led in runs scored with 152, and in 1887 was first in plate appearances with 677 and at-bats with 627. He added 129 stolen bases, second to Cincinnati Red Stockings right fielder Hugh Nicol’s 138. In 1888, Nichols stole bases 103 times, and Latham took 109 to come out on top.

Charlie Comiskey signed Latham to play for the Chicago Pirates in the new Players League for 1890, but left after 52 games and signed with Cincinnati, which had moved to the National League along with the Brooklyn Bridegrooms. After six seasons with the Red Stockings and a total of 340 stolen bases, Latham returned to St. Louis for eight games in 1896 while also spending time in the minors with Scranton (Eastern League – Class A) and Columbus (Western League – Class A). With Mansfield (Interstate League – Class B) in 1897, Hartford (Atlantic League – Class B), and New Britain (Connecticut State League – Class F) in1898, Latham returns to the majors with the National League’s Washington Senators for only a few games in 1899.

He tried his hand at umpiring on the side. Between 1899 and 1902, he was an umpire in the Interstate, Western and National Leagues.[1]

He can be traced to Denver (Western League) in 1902 and Jacksonville (South Atlantic League – Class C) in 1906, but in 1909 he was given the third base coaching job by John McGraw where his somersaults and comedic acts were a hit with fans.

Much of his statistical information is incomplete, particularly for his first two seasons in St. Louis and later minor league activity, but his reputation as carefree in baseball and everyday life caused him to be known as “The Freshest Man on Earth.”

In 1903 Latham was an umpire in the Southern Association, and his reputation for stealing the limelight from players continued into 1904.

“There’s no trouble in hearing a decision made by Umpire Arlie Latham. His voice is round and full, and he is not afraid to call out his decisions. That is as it should be. The people like to hear a decision. They want to know if it is a ball or a strike, or whether a runner is safe or out. Arlie is a little impulsive, however. He should control his temper, and not be too hasty.”[2]

By July, Nashville manager Newt Fisher had seen and heard enough as his club struggled to make .500 in the standings. Little Rock came to town for a four-game set on July 23 as Nashville was 35-38 in fifth place behind New Orleans, Memphis, Little Rock, and Atlanta.

Nashville won the first three to round out their record at 38-38, but not without boisterous rhubarbs and cat-calling. In the fifth inning and the score knotted 1-1, Jay “Doc” Andrews stepped to the plate for the home team. Latham called a few strikes for which Andrews did not agree.

“Jay was hot. He stamped his feet, clenched his teeth, threw down his bat and said things to “Mr. Umps” that were not in the Sunday school books.”[3]

Latham called for Fisher and told him Andrews must leave the game, which caused the Nashville manager to argue with the umpire that his third baseman should not have been given the old “heave-ho.” Latham took issue with Fisher’s arguing and called for the police to escort him out of the ballpark, which they refused to do.

“He boiled with rage and finally walked over to the bench where Fisher and the angry Andrews were sitting. The “rag chewing” continued, and final Sir Isaac Newton Fisher grabbed “Mr. Umps.” Then the cops grabbed both. The crowd yelled, “Hit the umpire; get an umpire; put him out; hit him, Fisher,” and such other gentle admonitions.”

Latham relented on Fisher’s expulsion and went back to calling the game. Eventually, Nashville won, 3-1, but afterward, the confrontation brought three explanations.

“I put Andrews out of the game because he was using profane language,” says Umpire Latham. “He had been giving the Umpires in the league a lot of trouble since he joined it a few weeks ago, and I had a letter from the President (Southern Association president William Kavanaugh) telling me to watch him. Such conduct as his is all wrong, and cannot do him any good. People come to see a ball game and not to hear a lot of kicking or to see a bull fight. I am going to do the right thing. I ordered Fisher out because he kept on kicking and arguing with me.”

Newt Fisher had his explanation.

“He should not have put Andrews out for what he did. It would not have made me so made except for the fact that before the game Latham had called Andrews a bad name; said he was going to lay for him and put him out the first change he got. That’s what made me sore. I am Captain of the team and certainly have a right to talk to the Umpire about a decision.”

Finally, Andrews confessed he had called Latham a name.

“He put me out because I kicked against his decisions, and I called him a skunk and told him he was ‘rotten.’ What’s a man going to do? Stand still and be robbed and have to take such decisions as he made?”

A final epithet from the newspaper explained how sportsmanship should be displayed on the field.

“The game was the kind it does a fan good to see, all except the wrangling. Players should not show their temper, and have no right to question the decisions of the umpire. On the other hand, the umpire should not try to be a Czar.”

Controversy followed Latham through the remainder of the season, and his contract was not renewed for 1905, a season he spent umpiring in the South Atlantic League. Perhaps his “Fresh” nickname continued to follow him throughout his career in baseball and beyond.

In England during World War I, he organized baseball for soldiers and was invited to Buckingham Palace to show King George V how to throw and catch. Latham remained in England for 17 years before returning to America in 1923, opened a delicatessen in Manhattan, and was a press box custodian for the Yankees and Giants.

The diminutive 5’8”, 150 lb. Latham died at the age of 92 on November 29, 1952, and is buried in Greenfield Cemetery in Hempstead, New York.

Writer Ralph Berger closes his Society for American Baseball Research biography of Latham with a testament to his popularity and talent.

“Latham’s passing resulted in a celebration of a man who did what he loved with a flair for the comedic. Until he passed away he had a sharp mind and a spryness about him that endeared him to anyone he met. Arlie was a great ambassador for baseball.”

Yes, he was except for one hot July evening in Nashville’s Athletic Park.

Note: In addition to baseball-almanac.com, baseball-reference.com, and sabr.org, the writer referred to Ralph Berger’s biography of Arlie Latham at https://sabr.org/bioproj/person/arlie-latham/

Sources

Nashville Banner

Nashville Tennessean

Newspapers.com

Notes

[1] “Umpire Artie Latham, A Famous Character in History of Baseball,” Nashville Banner, September 3, 1903, 7.

[2] “Another From Little Rock,” Nashville Banner, July 26, 1904, 6.

[3]Ibid.

© 2020 by Skip Nipper. All Rights Reserved.