Many recall the Shrine Circus at Sulphur Dell; how it entertained with clown parades and performers in the three rings laid out in the ball field. The finale was usually the Human Cannonball, and spectators oohed and aahed with the explosion of the cannon shot as his body hurtled through the air to a net erected to catch him before he landed on his head in the ballpark outfield and keep him from bouncing over the right-field fence into the ice house across the street in case of a miscalculated trajectory.

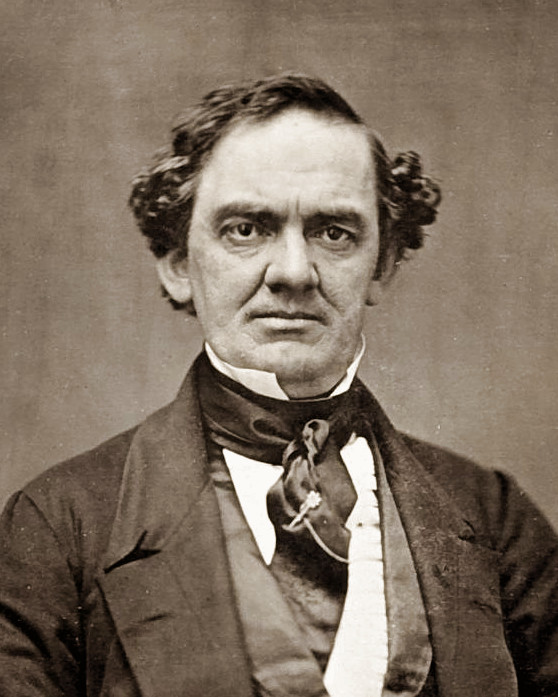

A reminder of those special nights comes in the form of a 2017 movie, The Greatest Showman, based on the life of P. T. Barnum, founder of the Barnum & Bailey Circus. It garnered a 3.5/4 review from film critic Sheila O’Malley[1] and widely accepted as a success.

Barnum proclaimed himself, “…a showman by profession…and all the gilding shall make nothing else of me…”[2]This king of the circus loved money so much that he often is credited with having said, “There’s a sucker born every minute,” which meant he was happy to separate anyone from the money in one’s pockets. His fame includes bringing a dwarf, General Tom Thumb, and the “Swedish Nightingale,” Jenny Lind, to his circus. His entourage toured Europe and many cities and towns in the United States in the middle of the 19th Century.

Nearly 40 years before becoming Sulphur Dell, the low-lying area north of Nashville’s downtown was called Sulphur Spring Bottom. It had a natural salt lick and sulphur spring, and many years before the city was founded, the area teemed with wildlife, especially buffalo and deer, who came to lick the mineral salt.

In the 1860s, the area was the city’s recreational grounds. It was there that baseball found its home, evacuated it 100 years later, and then reclaimed it in 2015 when the Nashville Sounds opened their new ballpark.

But in 1872, wild animals returned in the form of one of Barnum’s excursions named his “World’s Fair.”[3]

The exposition set up tents on Tuesday, November 12, for two days of performances after traveling from nearby Columbia, where Nashville’s Republican Banner said, “A very large number of people attended Barnum’s show at Columbia yesterday. It is said that his mammoth tents were well filled.[4]

With a warning that “The ‘Digger Indian’ in Barnum’s circus leaped down from his stand, while on exhibition at Elizabethtown, Kentucky, the other day, and gave a negro who had insulted him a sound drubbing”[5], the same newspaper gave a glowing recommendation by reporting “Barnum’s big show is now a topic of much discussion. It is likely to be better attended than anything of the kind that has appeared for years.”[6]

The newspaper also gave another warning on November 10.

“Reliable information has been received at Police headquarters to the effect that a large troupe of thieves, burglars, pickpockets, ebony legs and every conceivable kind of dishonest men are following Barnum’s circus around and as this will exhibit at Nashville Tuesday and Wednesday next, we are requested to warn our citizens in time that they may be on the look out [sic] for the visits of such characters as above alluded to.”[7]

Everyone expected thrills for adults from Barnum’s entourage, but it was the imagination of the young that brought great expectation.

The opening was a tremendous success and certainly made an impression on the minds of youth.

“Barnum’s big show is agitating the hearts of juveniles.”[8]

The Nashville Union and American also lavished praise on Barnum’s creation, “a brilliant and elaborate exposition that attracted universal attention and admiration” and “Great is Barnum.”[9]

But there was one Republic Banner report that did not initially seem positive in the exhibits’ substance.

“The stuffed whale, and that more stupendous stuff, the Cardiff Giants, were hardly worth transportation. Those “cannibals,” sentenced to death, from which fate the generous Barnum is to rescue them by the sacrifice of the pitiful $15,000 bond he is under to return them to the irate King of the Feejees; that “beautiful” Caucassian [sic], captured from some New York harem-scarem; the “sleeping beauty” (in wax) and other absurdities, were as cheap “curiosities” (as the interpreter of the ring phrazes [sic] it) as the little wooden automatons on Barnum’s portrait gallery.”[10]

In closing, the newspaper had to acknowledge the popularity of the big show and the mastery of Barnum’s ability to promote his business.

“And yet it drew like a house on fire. It drew because it was well advertised, and good people who protest that their business, which is genuine, does not draw, while Barnum’s, which is not so legitimate, does, should consult P. T., and see “what he knows about advertising.”

Soon reviews out of Columbia did not hold the same respect for Barnum, not for his exhibits, but for the crooks who followed the circus from town to town.

“We are requested by Dr. W. L. Matthews, to state that he, on the 8th of November, 1872, by the very efficient aid of Barnum and his band of thieves and pickpockets, was deprived, or hum-bugged out of the use of about $130 in currency, and also all his notes, accounts, etc. He hereby warns the public not to trade for any papers payable to him. He also requests us to say for the benefit of the lucky ones who were not present, that so far as pocket-picking was concerned, he challenges the world to be them.[11]

On the same day as the Columbia newspaper report, support for Nashville’s police force was made public. Perhaps Nashville’s finest had heeded the warning from the city Barnum had visited only days earlier.

Sadly Barnum’s New York museum and menagerie burned on the morning of December 24. Two elephants and a camel were the only animals to survive. Barnum was still on tour in New Orleans; his losses were estimated at over $100,000.[12]

P. T. Barnum, who was known primarily as a circus man, was an author, a newspaper publisher, politician, businessman, and indeed, a showman. He did not establish his circus until 1871, a year before it appeared in Nashville.[13]

Barnum died in 1891 at the age of 80. Perhaps in his only visit to Nashville, nearly 150 years ago, he once constructed his circus on the grounds we now hallow as Nashville’s historical baseball home.

Note: My wife Sheila and I saw “The Greatest Showman” on January 3, 2018. We thoroughly enjoyed it, and though not a professional film critic, I give the movie the best review I can: it’s a home run, hit far over the fence and out of the park.

Sources

Nashville Republican Banner

Nashville Union and American

Newspapers.com

Notes

[1] Sheila O’Mally, “The Greatest Showman”, RogerEbert.com, https://www.rogerebert.com/reviews/the-greatest-showman-2017, accessed November 3, 2020.

[2] Kunhardt, Philip B., Jr.; Kunhardt, Philip B., III; Kunhardt, Peter W. (1995). P.T. Barnum: America’s Greatest Showman. Alfred A. Knopf., 6.

[3] “Barnum’s Mammoth Show, Nashville Republican Banner, November 13, 1872, 4.

[4] “Sidewalk Notes.,” Nashville Republican Banner, November 9, 1872, 4.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Ibid.

[7] “Burglars, Thieves and Pickpockets,” Nashville Union and American, November 19, 1872, 4.

[8] “Sidewalk Notes.,” Nashville Republican Banner, November 13, 1872, 4.

[9] “Barnum’s Show.,” Nashville Union and American, November 14, 1872, 4.

[10] “What He Knows About Advertising.,” Nashville Republican Banner, November 14, 1872, 4.

[11] “Over the County,” Columbia Herald, November 15, 1872, 3.

[12] “New York. Barnum’s Menagerie Burned Again,” Nashville Union and American, December 25, 1872, 1

[13] Sarah Maslin Nir and Nate Schweber. “After 146 Years, Ringling Brothers Circus Takes Its Final Bow,” https://www.nytimes.com/2017/05/21/nyregion/ringling-brothers-circus-takes-final-bow.html, accessed November 14, 2020.

© 2020 by Skip Nipper. All Rights Reserved.