In August of 1960, Nashville’s return to the Southern Association for another season looked dim when Cincinnati withdrew the six-year affiliation it had with the Vols. In fact, the entire league had no assurance it would return for another year. It recovered by adding the Macon Peaches to fill the void that was left when Memphis exited.

The return of the Southern Association for 1962 looked even more bleak. Attendance went from 780,316 in 1960 to 647,831 in 1961, a decline of 17%. Television and air conditioning are often blamed for the lower turnout, but there may have been a deeper, more profound reason.

Gabe Paul, general manager of the Reds, explained the decision to drop Nashville from the farm system plainly. Bottom line: No Black players equals no proper development of potential players equals the agreement ends.

No Stance Taken

For an entire year, no stance was taken by Nashville nor any other ball club in the league. There would be no integrating of the Southern. There was no vote taken either way, no ultimatum passed down from league or team leaders, no public protests by fans that would discourage continued segregation.

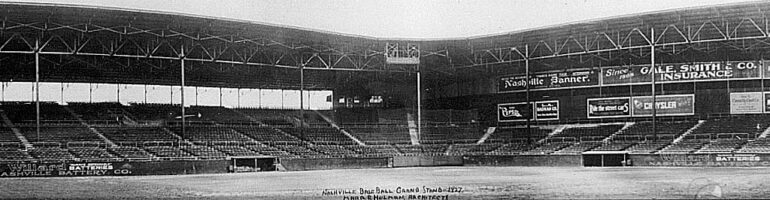

What saved the Vols franchise for one last season in the Southern Association? Enter the Minnesota Twins. Formerly the Washington Senators and relocated to the Twin Cities, the major league club was so profitable in their new home that stockholders received a $2-a-share dividend[1]. Not exactly keen on Nashville or its ballpark, Sulphur Dell, farm director Sherry Robertson had not given up hopes that Montreal, not the Vols, would be the new affiliate for the Twins.

“We would go into the Southern Association only as a last resort,” he told the Minneapolis Star. “In the first place, the Southern is a double A league and we need a triple A farm. Nashville’s park isn’t good place to develop players.

“And then, and this is important: The Southern bars Negroes, and we have several. That is one of Nashville’s biggest problems in getting an agreement. If a club can’t send its Negro players there, it doesn’t want the tieup[sic].[2]

He was right, sort of. Although there was no edict to “ban” or “bar” Black players, there certainly was no edict to the opposite. And this is 15 years after Jackie Robinson had signed to play for the Brooklyn Dodgers.

Minnesota Twins to the Rescue

Twins management offered a deal on January 23, 1961, to partner with the Nashville ballclub and stock the team with players. Not only did the arrangement save the Vols, but it also saved the Southern Association. The agreement included points which league president Hal Totten hoped would be a part of future major league affiliations in the Southern:

According to the previous agreement with Cincinnati, Nashville had been paying up to $750 a month for optioned players’ salaries, and all salaries of players on outright assignment.[3]

The 1961 season was salvaged, but by August Nashville wallowed in the bottom half of the Southern Association standings. The club featured a makeshift roster, as the team featured only five players who had seen, or would see, action in the big leagues: Buddy Gilbert, Gene Host, Rod Kanehl, Joe McCabe, and John Romonsky.

On the night of August 11, Twins Executive Vice-President Joe Haynes and Robertson visited Sulphur Dell (for the first time) to take stock of Nashville’s players. The major league club was looking for those worthy to call up to the fold, as the Twins were going nowhere but seventh place in the 10-team American League.

It turned out to be a special night for Vols left fielder Joe Christian, who had been sailing along with a .329 batting average and had eight home runs. He added another home run and two singles for four RBI, and now had 220 total bases for the year. Ev Joyner added a home run and single, driving in four runs, and Gilbert hit two doubles, a single, and a sacrifice fly, good enough for five RBI.

None of the three were the property of the Twins.

The Vols won the game over the Birmingham Barons, 16-7, and even though they were outhit 22-12, Nashville pulled off five double plays to seal the win, the Vols’ fifth straight. There were 721 paid admissions in the stands.

The attendance nor final score were the most important news of the night. Comments by the Twins’ Robertson were.

Must Play Black Players

He told Nashville Tennessean sportswriter F. M. Williams the future of the minor leagues looks good, except for two leagues. When Williams asked which ones were in trouble, Robertson identified the Southern and Western Carolina leagues.

“You people have got to play Negroes to remain in business,” he added.

Williams asked if the unofficial ban were to be lifted, would the outlook change. Robertson’s answer?

“Definitely.”

“Robertson said it is too early to discuss continuation of the working agreement with Nashville. But he intimated the Twins do not have enough ball players to staff a Double A club in the coming years.”[4]

What he was saying was the Twins did not have enough white players to send down to Double A.

Finally, the 50-man board of directors of Vols, Inc., representing 4,876 stockholders, heard him loud and clear, and acted on the controversial measure.

Meeting at Nashville’s Noel Hotel on September 2, the board voted unanimously to use Negro players in 1962, although a few grumbled about the matter.[5] But even those few were not going to jeopardize Nashville’s chance to go fail, possibly risking their investments in Vols, Inc. stock.

In the meantime, Robertson was certain some arrangement could be made to save Nashville.

“We can’t afford to let the Southern League die. We don’t have enough ball players to furnish a team in Nashville, but we will work something out, I am sure, at the meeting of farm directors tomorrow morning.”[6]

Robertson offered up a new idea to include Nashville as a part of the Twins organization. It involved a dual working agreement with the Pittsburgh Pirates. When the Pirates reneged and Columbus showed interest in placing a team in the league to replace Macon, Minnesota suddenly joined up with the Georgia club. Macon was a victim of big operating losses in 1961.

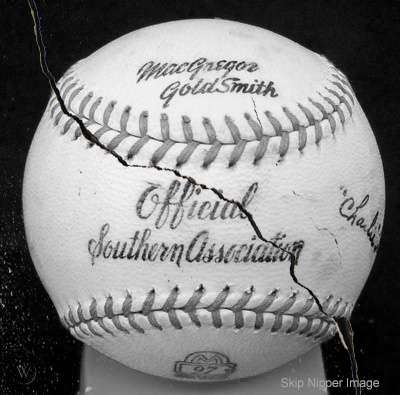

Coming Apart at the Seams

Birmingham decided to pull its club over the use of Negroes; the Detroit Tigers, the Barons major league affiliate, had little choice but to associate with Nashville should the team and league stay in business in 1962. It did not happen, and one player did not get a chance to integrate Nashville or the Southern Association.

A few months after the end of the 1961 season, minor league clubs met in Tampa for their annual winter meetings, and Nashville general manager Bill Harbour stood by his board’s decision to include Black players. John Dee Griffin, a catcher who appeared in 76 games and had a .183 batting average for Fox Cities in the Three-Eye League (Class – B), was drafted by the Vols.[7]

When the Vols went defunct for the 1962, Griffin ended up with Elmira (Eastern League – Class A). He had a 10-year career, all in the minor leagues, reaching as high as Class AAA ball with Rochester, Oklahoma City, and Arkansas (Little Rock) from 1963-1965, even playing in the Southern League with Chattanooga in 1965 and Macon in 1966. He finished his professional career in 1967 with Amarillo (Texas League, Class – AA) and Salem, Virginia (Class – A).

Southern Association Disbands

The Southern Association met its end, never to be resurrected again. After one season with no professional baseball, Nashville returned in 1963 as a member of the South Atlantic “SALLY” League (Class – AA), which was integrated. It was that year that Eddie Crawford and Henry Mitchell, both Black people, were on the Vols roster; the first two and only of their race to perform for the team.

Hall of Fame baseball executive Branch Rickey, who signed Robinson to his Dodger’s contract, once said, “Ethnic prejudice has no place in sports, and baseball must recognize that truth if it is to maintain stature as a national game.”[8]

The teams in the Southern Association, Nashville included, missed an opportunity to boost the inevitable integration of minor league baseball in their cities until it was too late. The truth, as we now know, set them all free.

Sources

Baseball-reference.com

Newspapers.com

Paper of Record

Sabr.org

Southernassociationbaseball.com

Wright, Marshall D. (2002). The Southern Association in Baseball, 1885-1961. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Co.

Notes

[1] Raymond Johnson. “One Man’s Opinion,” Nashville Tennessean, January 20, 1961, 28.

[2] “Nashville Seeking Tieup with Twins,” Minneapolis Star, January 19, 1961, 36.

[3] F. M. Williams. “Twins Tieup Rescues Nashvols,” Nashville Tennessean, January 24, 1961, 11.

[4] Williams. “Southern Outlook Bleak – Robertson,” Nashville Tennessean, August 12, 1961, 15.

[5] Williams. “Vol Directors Vote to End Ban on Negro Players in Sulphur Dell,” Nashville Tennessean, September 3, 1961, 27.

[6] Williams. “Dual Agreement Expected for Nashvols,” Nashville Tennessean, November 29, 1961, 18.

[7] “Vols Draft Negro Player,” Nashville Tennessean, November 28, 1961, 18.

[8] “Branch Rickey Quotes,” Baseball-Almanac.com, http://www.baseball-almanac.com/quotes/quobr.shtml, accessed August 14, 2017.

© 2022 by Skip Nipper. All Rights Reserved.

The Three Eye League is the Three I League. It consisted of teams from Indiana, Illinois, and Iowa.

Correct. However, “Three-Eye League” is acceptable and was often used, such as: “The league began play in 1901 and disbanded after the 1961 season. It was popularly known as the Three–I League and sometimes as the Three–Eye League.” Here’s an example from the New York Times in an article entitled, WANTS BASEBALL MEETING.; President of Three-Eye League Would Cut Players’ Salaries: https://www.nytimes.com/1916/12/08/archives/wants-baseball-meeting-president-of-threeeye-league-would-cut.html Thank you, Skip